It’s an unlikely story. Serious and highly regarded reporter writes a memoir that details not the horrors of war nor the vicissitudes of political journalism, but the arcane minutiae of a parallel life spent surfing. Somehow he manages to make it intelligible and interesting to a general readership. Even more improbably, he does so without losing credibility among other surfers. The book wins a Pulitzer Prize — the first, and surely the last, to be won by a piece of surf writing — and is included on then-President Barack Obama’s summer reading list.

But then the story William Finnegan had to tell wasn’t a particularly likely one either, even if the full extent of its unlikeliness has been lost on most non-surfing readers. Perhaps surfing double-overhead Honolua whilst off one’s tits on acid was par for the course among sunburnt pagans in the 1970s, but probably not. And stumbling across the island of Tavarua certainly wasn’t, turquoise-tinted glasses notwithstanding. In his mid ‘20s, Finnegan became one of the very first surfers to ride the wave later named Restaurants. He and his friend Bryan Di Salvatore — who in another unlikely coincidence would end up, like Finnegan, on the staff of The New Yorker — had it to themselves for weeks.

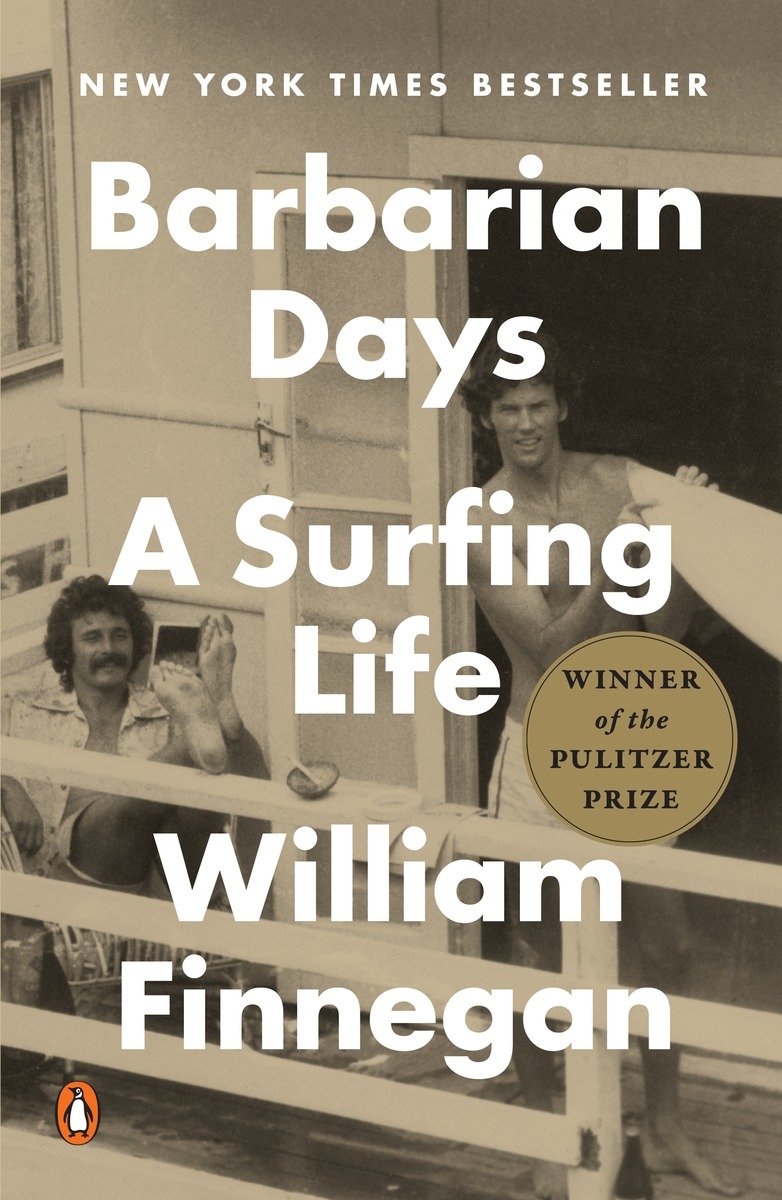

It was the scoop of the century, although it wasn’t until six years later that, despite their best efforts, and much to their annoyance, it hit the front pages, Tavarua splashed across the cover of Surfer’s December ’84 edition. Since then, Finnegan has added to his role of secret keeper that of secret sharer. Apart from his classic 1992 New Yorker piece “Playing Doc’s Games”, and the award-winning Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, he has largely avoided writing about surfing. Instead he has reported on apartheid in South Africa, war in Mozambique and Sudan, drug trafficking in Mexico, human trafficking in Moldova, poverty and cultural conflict in the United States. If President Trump had a reading list, Finnegan would not be on it.

Which brings us nicely round to the subject of barbarians, and the many contradictions entailed by that word and its variants. In the closing paragraphs of The Malay Archipelago, his 19th century account of scientific discovery in Indonesia and thereabouts, the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace concluded that the West could claim no “real or important superiority over the better class of savages”. “Compared with our wondrous progress in physical science and its practical applications,” he wrote, “our system of government, of administering justice, of national education, and our whole social and moral organisation, remains in a state of barbarism.” Finnegan — who has conducted research of his own in the Malay Archipelago, and for whom the critique of our social and moral organisation has long been a central concern — has characterised surfing as “a track that led away from citizenship, in the ancient sense of the word, toward a scratched out frontier where we would live as latter-day barbarians.” And what was it Morrissey said on the matter, in The Smiths’ superbly titled “Barbarism Begins at Home”? “Unruly boys who will not grow up must be taken in hand.”

Finnegan grew up eventually, but only after a fashion. Indeed, Barbarian Days is in large part a chronicle of his struggle to square the unruliness of youth with the responsibilities of adulthood and citizenship.

He was recently in Europe and San Sebastián, where he collected a literary prize awarded by Basque Country booksellers, and later spoke at the city’s aquarium at the invitation of the council. After the talk, I found him in a dimly lit aquarium corridor as he contemplated a particularly venomous scorpionfish. He gave me an email address and some learned advice about the dangers of tropical sea creatures. Worried that he might be tiring of long-winded interviews about his most recent book, I foolishly attempted to steer things in the direction of puerility, sending him a list of brief and desultory questions. I was duly taken in hand. “These questions, not to put too fine a point on it, are shite,” came his reply. He kindly invited me to send him some more, resulting in the following exchange.

*****