Interview by Daryl Mersom

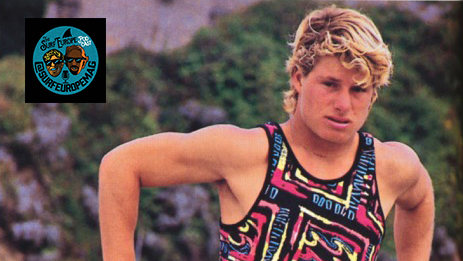

Photography by @alanvangysen

“When I was born I was on the front page of the newspapers because my dad gave me a Zulu middle name, Thulani. Death threats were sent to my dad saying, ‘You might love the black man – but don’t be so savage and put this on your son.’ ”

I am sitting with South African pro surfer Beyrick De Vries in his seafront apartment. Outside we can hear Dutchie’s booming commentary of The Ballito Pro vie with the crashing Indian Ocean.

This is a country with a complex recent history, where naming a child is a political act. The name Beyrick Thulani De Vries, which splices Dutch and Zulu together, was given to the surfer by his father Ray, after Ray’s experiences training Willie Mtolo, the first South African to win the New York Marathon in 1992, with a time of 2:09:29.

Willie’s achievement preceded the end of apartheid by two years (it was officially brought to an end in 1994 through the election of a non-white coalition) and flouted the sporting embargoes placed on South Africa. In fact, he was only able to compete because Beyrick’s father owned a hotel in Hillcrest and let black athletes stay there free of charge.

Shortly after Willie’s victory, Beyrick’s mother found out that she was pregnant. Because of this fateful timing, the child’s name would be inextricably linked to the political moment of 1992.

“All of the Zulu and Xhosa guys from the different tribes have English names in South Africa, but the white guys don’t have to have Zulu names. Willie questioned my dad about this, and consequently, my parents gave me the name ‘Thulani’ – which means the quiet one, and is of course terribly inappropriate”, Beyrick tells me with a smile.

“We’ve still got the photograph framed of my dad holding me with all of the press trying to get photos because this young white boy is called ‘Thulani’. The world saw this all happen. Willie went to meet the president and America loved it. This was a person who wasn’t allowed to go to the same beaches as a white person. It seems ridiculous to us now”.